Nigerian American author Nnedi Okorafor is a name fantasy fans are well familiar with—she’s won Hugo, Nebula, World Fantasy, Locus, and Lodestar Awards—and an even bigger audience awaits, since her Who Fears Death is being developed into an HBO series. In November, she’ll release Like Thunder, the sequel to Shadow Speaker in her Desert Magician’s Duology. io9 has a sneak preview to share today!

Here’s what Like Thunder is about:

This brand-new sequel to Nnedi Okorafor’s Shadow Speaker contains the powerful prose and compelling stories that have made Nnedi Okorafor a star of the literary science fiction and fantasy space and put her at the forefront of Africanfuturist fiction

Niger, West Africa, 2077

Welcome back. This second volume is a breathtaking story that sweeps across the sands of the Sahara, flies up to the peaks of the Aïr Mountains, cartwheels into a wild megacity—you get the idea.

I am the Desert Magician; I bring water where there is none.

This book begins with Dikéogu Obidimkpa slowly losing his mind. Yes, that boy who can bring rain just by thinking about it is having some…issues. Years ago, Dikéogu went on an epic journey to save Earth with the shadow speaker girl, Ejii Ubaid, who became his best friend. When it was all over, they went their separate ways, but now he’s learned their quest never really ended at all.

So Dikéogu, more powerful than ever, reunites with Ejii. He records this story as an audiofile, hoping it will help him keep his sanity or at least give him something to leave behind. Smart kid, but it won’t work—or will it?

I can tell you this: it won’t be like before. Our rainmaker and shadow speaker have changed. And after this, nothing will ever be the same again.

As they say, ‘Onye amaro ebe nmili si bido mabaya ama ama onye nyelu ya akwa oji welu ficha aru.’

Or, ‘If you do not remember where the rain started to beat you, you will not remember who gave you the towel with which to dry your body.’

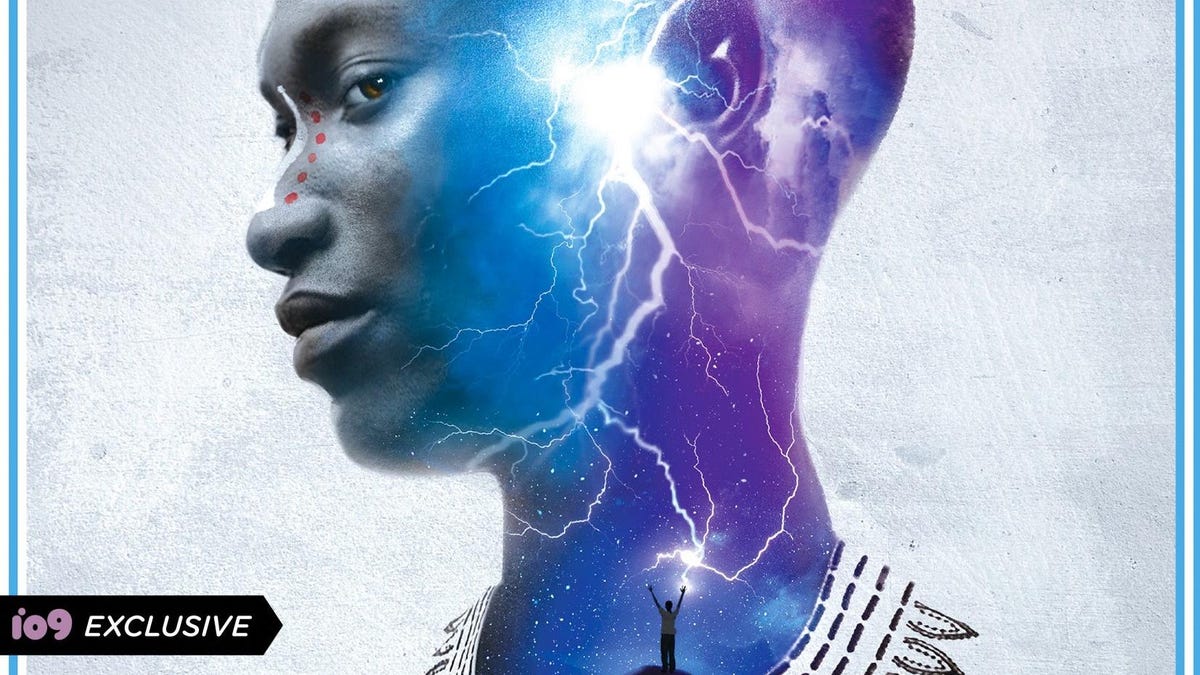

Here’s the cover, making its debut here on io9; the cover illustration is by Greg Ruth, and the cover design is by Jim Tierney. An excerpt from Like Thunder follows.

Translating . . .

Dikéogu Audio File Series

begun April 8, 2074

Current Location: Unknown Region, Niger

Weather: 36o C (98o F), N.I.U.F. (Not Including Unpredictable Factors)

This audio file has been automatically translated from the Igbo language.

Rainmaker

My name is Dikéogu Obidimkpa. I am a rainmaker. Born in Nigeria but made elsewhere. The tattoo on my face is red and white, the colors of Shango, god of thunder and lightning. My tattoo turned those colors on its own. It used to be blue. Shango’s colors suit me better.

I dictate this account of all that happened after everything has happened. But it’s all still happening. You’ll understand as you listen. For me, stories never end. I recorded these specific files that I titled “Rainmaker” when I was or am having an especially camelshit type of day. When it’s hard to think, when I feel like I’ll just blow apart or blow away. Making these files help. Sort of. In a blood-letting kind of way. So if I sound different in “rainmaker” files, you’ll understand why.

A storm came today. It blew in out of nowhere, but I knew it was coming. I always know when a storm is coming. It snapped palm trees like matchsticks. Threw a scooter like a sack of stockfish. It soaked the sand and grass like Noah’s flood. It washed rooftops. It was noisy and glorious.

But I spent that half hour on the dirt floor of this small house with all the lizards, spiders, and centipedes. No one could speak to me. No one could touch me. Only Gambo would have understood.

When I closed my eyes, I saw huge rolling gray clouds. I could smell the land’s fragrance rise up just before the rain came. I could smell the clouds as lightning ionized water vapor. I could feel the air pressure drop and then rise.

I was splashed with millions of raindrops. I could feel what could have been. The destruction. The power. I could hear the rain and thunder, outside. First the patter of sand on grass and leaves and then the splash of mud. The howl of wind.

And when I opened my eyes, I wanted to flee. But I couldn’t. Not anymore. I am in fear’s chasm. Okay, maybe Ejii would understand, too.

My hands tremble just thinking about it.

I can’t change what I am.

I am a rainmaker, but mostly it rained on me.

Don’t wish to be me. Or to be able to do what I do. What I can do can be done to me when the sky merely wills it.

CHAPTER 1

Better Told Than Written

I’ve seen so much.

I want you to imagine it.

So, as I said, I’m recording my words as an audio file on this damn near indestructible e‐legba, a piece of portable tech so strong it outlasted the apocalypse. Sure, it looks pretty beaten up. That’s because it’s taken quite a beating. But no other personal device could do all that this one does, trust me. Recording something doesn’t even raise its processor usage level, not even by a fraction. And it’s both solar and lunar. This recording will last.

Some things are better told than written. Maybe the old Africans had it right in initially making their traditions oral. Plus I’m more of a talker than a writer. I don’t have the patience to spend hours tapping on keys. Plus out here in the middle of the desert, I kind of like the sound of my voice.

And I’m an honest guy, not some mumu guy. Of all people, I don’t believe in gossip. Gossip is what got me in this mess in the first place. You can trust me. It’s okay to let your guard down. I’ll tell you no lies. No exaggerations. Fear no ego. No need for suspension of disbelief. This all happened and God help me now.

My friend Ejii liked to laugh about how I barely trusted anyone. She liked to exist in the naïve‐nice‐person‐land where all humans, deep down, are good. I wonder what she thinks now, after so many have proven themselves to be cowards, liars, cheats, murderers, and lackadaisical pacifists who are happy to sit and watch innocent people die terrible deaths. Yeah, I said it. Someone has to. I know what I’ve seen. I know what I’ve had to do. And yeah, this thing is recording.

The Great Change was this weird combination of a nuclear apocalypse and the explosion of powerful juju called “Peace Bombs.” This messed up many of Earth’s laws of physics and brought down the wall between worlds. Then there was a pact of peace. It was written by noble genius baboons with black hands and soft brown fur that smelled like mint and grass. They wrote the pact in a magical language called nsibidi. This pact forced a truce between the evil inflated Chief Ette of Ginen’s Ooni Kingdom and the insanely heroic Jaa the Red One of the Sahara Desert. It stopped a war of the worlds, especially between Earth and the jungle planet Ginen. I’m damn proud to say that I was there and a part of why the pact was successful. So was Ejii, of course. She was a big deal that day.

That pact was some serious, deep, old mysticism. Even after all I’ve seen, I still find it amazing. That it happened at all is unbelievable. That it lasted for so long was nothing short of a miracle. For a few months it kept the monster of war still, and for three years it held it at bay. But the pact eventually disintegrated, as it had to. But so did a lot of other things.

How do I explain all that happened? I’ll make it simple: eventually, all hell broke loose . . .

CHAPTER 2

Chocolate Factory

Right after the historical pact was made, I had important business to take care of. One problem solved (temporarily, at least), so on to the next one. I was focused, as was my owl Kola. And so was my mentor Gambo.

We all had reasons for going on this mission. For Gambo and me, it was because we’d both actually experienced slavery firsthand. Buji, Gambo’s co‐husband, was just a man who revered justice. When Buji saw injustice, he had to do something about it. The Nigérien Bureau of Investigation, a.k.a. the N.B.I., came with us because they were trying to cover their asses and not look like asses. As if they could prevent that. All these years and they knew nothing about what was happening in the northern part of what used to be Niger? Camelshit. They knew. And now they knew that if they didn’t do something they’d suffer hard‐core sanctions and boycotts.

Gambo, Buji, Kola, and I had just left Ejii and Jaa in Kwàmfà. I was so excited to be going north with these people. After all that had happened. Toward this specific place. A place I hated.

Assamakka.

This place used to be a small innocent desert city with mazes of mud‐brick homes, camels, goats, desert birds, scurrying lizards, women pounding millet, men kneeling in prayer. But after the Great Change, when nuclear and Peace bombs fell and huge swaths of land here shifted from dead sand to lively sand and soil, opportunists made it the central headquarters of the cocoa industry. Most of the world’s cocoa used to make chocolate came from Assamakka and the farming towns around it. And all these places used cheap labor. Really cheap labor. Cheap young labor. Child slaves.

There is definitely a reason I hate chocolate. I’ll always hate it. I’d rather die than eat it. Chocolate was mixed with blood, sweat, and tears of children. It was a haunted confection. Way way back in 2003, Niger passed a law making slavery illegal. And even before that there were laws against child labor. These did nothing to stop it, though.

Even with all the spontaneous forests and new worlds and people and creatures dying and changing all over the place . . . you could still get chocolate. Anytime, anywhere. Common brown blocks of smooth delicious pleasure. Melted or solid. But no one wondered where it came from. How surprised you all would have been, o.

All I have to say about the land along the way is that it was dry, cracked, and full of nasty aggressive red beetles that tried to burrow into our tents at night. And they stained whatever you crushed them on. That didn’t stop me, though. I had garments stained with red dots to prove it.

This was just before we met up with the N.B.I. We didn’t see any spontaneous forests and the weather was acceptable— meaning it was harsh and hot during the day but cool at night. Gambo and I wouldn’t have meddled with the weather regardless, even if we came across a severe storm. Even before we’d set out for Assamakka, he’d made sure to teach me that one should alter the weather sparingly or work with the will of nature.

“It’s irresponsible to do otherwise,” he said in his usual low rumbly voice. “A rainmaker who thinks he owns the sky is a rainmaker soon painfully killed by rain, snow, lightning, hail, or all of the above.”

About two days later, we stopped at a market for supplies— a second capture station for water, some new tents (those vile red beetles had eaten through two of ours), green tea, dried meat (a group of desert foxes had stolen much of ours), salt for the camels, a bag of millet to make tuagella (those thick crêpes that you eat with butter or sauce).

I remember all this because this turned out to be the last time we were in civilization for months. It was also where I bought this e‐legba that I’m using to record my voice. Ejii had one that she liked to use to check the weather, play games, read books, and listen to music. I believe she lost it on the way to Ginen, though.

I used to have an expensive one back in my old life, before my parents sold me out. This new one that I got at the market wasn’t nearly as pricey, but I wasn’t complaining. It did what it needed to do. Of course, the e‐legba I bought was nothing like the souped‐up device it is now. Not yet.

We continued on our way, and what would happen next would shape everything that led me to where I am today.

About a day after leaving the market, we met up with a man named Ali Mamami. He was the head of the Nigérien Bureau of Investigation. He was a pretty intense guy. Ali liked to wear flowing garments that were so voluminous that you couldn’t tell if he was skinny or fat. He never smiled. He didn’t add sugar to his mint tea or use salt with his meals. He didn’t listen to music. The man was like petrified wood. You wonder what someone like that has seen to make him that way. But I didn’t think he was so impressive. He’d missed what was going on in the north, for Christ’s sake. Still, I kept out of his way.

With him came twenty N.B.I. agents—men and women specially trained for this kind of thing. Before the Great Change, they’d have all carried big guns. These people, how‐ ever, carried machetes, Tuareg‐style swords called takoba, and high‐tech bows and arrows, and were trained in hand‐to‐hand combat and wore weather gel–treated uniforms and army boots (you did not want to be near any of their feet when they took those boots off). Two women even had a pair of those Ginen weapons called seed shooters.

My friend Ejii had told me about these, but I’d never seen one until one of these women showed me. They look like hand‐sized greenish brown disks with a notch on the side for your fingers. And they were very light. The woman, her name was Nusrat, clasped it in her hand as she faced the desert, the end of her brown veil over her head fluttering in the breeze. The other woman, Hira, wore a veil over her head, too. I assume they were both Muslim. Or maybe they just liked the attire; you never know.

Nusrat grinned, obviously enjoying demonstrating.

“It feels hard but it’s alive, a plant,” she said. Her voice was kind of low. If it weren’t for the enormous size of her chest (you couldn’t miss it, even with the uniform) and her face (okay, she was quite attractive), I’d have speculated that she might have been a man. She had an intensity that reminded me of Gambo, and there’s nothing remotely feminine about Gambo.

Nusrat took my hand and held it to the seed shooter. As soon as my hand touched it, it changed from greenish brown to dark brown as if it were some sort of plant chameleon. “It responds to touch,” she said, laughing. “It doesn’t like you. For some reason, seed shooters prefer women. The accuracy is always better when they are used by women. Be very afraid if you come across a man with one, especially if you’re not his target.”

I frowned, thinking of those giant flightless birds Ejii had ridden in Ginen. They supposedly didn’t let boys or men ride on them, either. Maybe things from Ginen preferred female humans to male ones.

“You stroke the side and it hums,” Nusrat said, rubbing the seed shooter. It made this sound that was oddly like the purr of a cat. You could feel it, too. Like it was more animal than plant. I’d have thrown the thing away, but I wanted to know what it felt like when it shot. “When you squeeze it,” she said, “your four fingers have to be touching this smooth patch on the front.”

She pointed the seed shooter at the ground, aiming a few yards away, and squeezed my hand. I barely felt or heard a thing. Just a soft phht as something reddish orange blasted into the sand. Then there was a sort of oatmeally smell. POW! There was a small explosion in the sand as the seed popped like a large popcorn kernel. Some big green beetles emerged from the sand nearby and frantically scrambled away. Imagine what that seed would have done if the seed were embedded in someone’s chest, leg, arm, or . . . head.

She strapped the thing against the bare skin of her side, pulling her uniform over it. Seed shooters produce more seeds by feeding on body heat. Needless to say, those two women were probably the most lethal N.B.I. agents in the Sahara be‐ cause of their skill and those weapons.

I smiled. Lethal was what I wanted.

Excerpt from Nnedi Okorafor’s Like Thunder reprinted by permission of DAW.

Like Thunder by Nnedi Okorafor will be released November 28; you can pre-order a copy here or here.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.